Table of Contents

Executive Summary…..2

History…..2

Mission Statement…..3

First Two Years: January 1, 2021 – December 31, 2022…..4

Research, Training, and Outreach…..4

Program Policy and Procedure Development…..5

Contact Data and Statistics…..6

Numbers and Types of Contacts…..6

Type of Requests…..7

Requests by County…..8

Trends…..9

Success stories…..10

Barriers to Investigations…..11

Recommendations…..11

Legislative…..11

Summary…..12

Glossary of Acronyms…..14

Appendix…..15

Enabling legislation

Executive Summary

Welcome to the inaugural report of the Office of the Child Welfare Ombudsman (CWO), a program created by the Arkansas General Assembly to provide for independent oversight of the child welfare system in Arkansas. This annual report is mandated by the enabling legislation, Act 945 of 2019 sponsored by Senator Alan Clark. The reporting period includes activities of the CWO office for the calendar years 2021 and 2022.

History

The Child Welfare Ombudsman Division was created by the 92nd General Assembly and housed within the Arkansas Commission on Child Abuse, Rape and Domestic Violence (ACCARDV); an agency with more than two decades of child welfare experience, while being uninvolved in the investigative, administrative or judicial handling of child maltreatment cases. This allows the CWO to function independently of the Department of Human Services, Administrative Office of the Courts, Commission for Parent Counsel, Attorney Ad Litem Program, Arkansas Public Defender Commission and Arkansas Court Appointed Special Advocates as mandated by A.C.A. 20-82-211(a)(5)(A).

The Arkansas Commission on Child Abuse, Rape, and Domestic Violence (ACCARDV) was established in 1991 to enhance the coordinated approach in providing services to victims of child abuse, rape, and domestic violence.

Today the mission of ACCARDV is to enhance investigation, prosecution, treatment, support, and prevention in cases of child abuse, rape, human trafficking, and domestic violence. ACCARDV fulfills this mission through a collective impact approach consisting of two arms that work together to enhance victim services around the state. There are 22 Commissioners appointed by the Governor who serve as an advisory council and representatives of their communities and interests surrounding violence and abuse. The Commissioners work in the areas of focus or have experience with one or more of the issues. They convene triannually to discuss the Commission goals, projects, and strategies to help the people of Arkansas.

ACCARDV staff carry out the projects of the Commission by leading work groups, obtaining and administering funding, analyzing gaps and barriers, advocating for individuals, identifying needed access, looking for policy and funding solutions, and bringing together advocates and service providers to develop solutions. ACCARDV staff members work closely with other state level service-providers and collaborate with Commissioners to ensure that all areas of the continuum are being met across each of the Commission’s focus areas. ACCARDV is housed within the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) which allows for integration and the support of other departments and colleges.

The first Child Welfare Ombudsman was hired by the Executive Director of ACCARDV in December of 2020, and the office officially opened on January 11, 2021. In September of 2022, the Ombudsman moved into the position of the Executive Director of ACCARDV and hired a new Child Welfare Ombudsman. This report covers the data from cases handled by both of the Ombudsman Directors.

The Child Welfare Ombudsman Division is funded primarily through a contract with the Department of Human Services and supported by additional funding from the Children’s Justice Act (CJS) Grant. Staff funded by the CJA Grant assists the CWO Division with policy and legislative research as well as collaboration with the Child Welfare Committee, a standing committee within ACCARDV including representatives from the following agencies and disciplines:

- Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS)

- Arkansas Children’s Hospital

- Family Treatment Program

- Attorneys ad Litem (AAL)

- Parent Counsel

- Court Appointed Special Advocates

- Child Advocacy Centers of Arkansas

- Arkansas State Police

- Arkansas Building Effective Services for Trauma (ARBEST)

This committee also convenes a child welfare legislative workgroup prior to each non-fiscal legislative session to share potential legislation prior to filing bills. The Child Welfare Ombudsman will have an opportunity to share recommendations with the workgroup based on cases reviewed by the CWO Division, as well as provide unbiased recommendations on draft legislation presented by other agencies and disciplines involved in the investigative, administrative and judicial handling of cases.

Mission Statement

The mission of the Child Welfare Ombudsman office is to review an issue or complaint in any child welfare case or investigation in which a child or their family needs assistance from the Ombudsman; to bring resolution when possible; and to advocate for policies and procedures that will improve the child welfare system in Arkansas.

First Two Years Overview: January 1, 2021 – December 31, 2022

Research: Information was gathered from other states on Child Welfare Ombudsman practices, procedures, and data collection. Complaint forms and brochures were developed and disseminated through the ACCARDV website, mailouts, and handouts at conferences and meetings. Guidelines and best practices were gained from the United States Ombudsman Association (USOA) https://www.usombudsman.org and set forth as the best practices for the Child Welfare Ombudsman Office. Those guidelines are:

- Independent. An Ombudsman office should be free from outside control or influence.

- Impartial. An Ombudsman should receive and review each complaint in an objective and fair manner, free from bias, and treat all parties without favor or prejudice.

- Confidentiality. The Ombudsman should have the privilege and discretion to keep confidential or release any deindentified information related to a complaint or investigation.

- Credible Review Process. The Ombudsman should perform his or her responsibilities in a manner that engenders respect and confidence and be accessible to all complainants.

More information can be found at https://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/childrens-ombudsman-offices.aspx.

Training: The USOA provides training for new Ombudsmen each year. This training was attended virtually in December 2021. A session on Child Welfare Ombudsman Offices was provided at the National Association of Counsel for Children Annual Conference. This session was presented by the Child Protection Ombudsman of Colorado and the Child Welfare Ombudsman from Washington state. Monthly meetings of the USOA Children & Family Chapter are attended virtually which provide trainings on issues and best practices for Ombudsman Offices. The Arkansas Ombudsman joined USOA in November 2021. All new Ombudsman employees are required to join and participate in USOA meetings. New Ombudsmen will also attend New Ombudsman training when available.

Outreach: The Ombudsman reached out to stakeholders within the Child Welfare Community throughout the year through virtual meetings of the Commission, presenting at the Attorney Ad Litem conference and the Association of Juvenile Officers conference, visits to domestic violence shelters throughout the state, providing brochures and information packets to all Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) coordinators throughout the state, developing a website presence on the ACCARDV

website, and visiting courtrooms and speaking with attorneys and judges that handle child welfare cases. Referrals to the Ombudsman office came from many sources, including but not limited to: Legislators, therapists, judges, attorneys ad litem, the DYS Ombudsman, and behavioral health facilities.

Outreach continued into the second year through mandated reporter trainings, meeting with foster parent support groups, and through visits to domestic violence shelters across the state. Information is shared whenever the opportunity arises to provide information to community groups and stakeholders. Word of mouth has also been a very successful way to get information to those who can benefit from the assistance of the Ombudsman office.

CWO Program Policy and Procedure Development

Responding to Requests and Contacts: The Ombudsman’s first case was received the afternoon the office officially opened and cases steadily increased throughout the year. Forty-three (43) cases were handled in the first year, and ninety-two (92) cases the second year. Some were closed within a day, while others remained open for review for several months. Requests for assistance came by phone, email, and complaint forms available on the ACCARDV website. Most complaints were responded to the day they were received, and at most within 48 hours. Depending on the complexity of the case and the amount of review required of DCFS records and contacts to parties involved, an investigation could take a few hours to several days or weeks. Complaints are addressed quickly, but due to the ongoing nature of many of the child welfare cases, the Ombudsman’s office will regularly review cases to make sure the issues arising in the complaint have remained resolved. In a few cases, the complainant will continue to reach out to the Ombudsman office throughout the course of their case for assistance with issues that arise.

The majority of cases during the reporting period were categorized as follows:

- Not Accepted/Referral Only: Requests for assistance without a prior Hotline report or an open dependency-neglect case are outside the current legislative perview of the Ombudsman Office. However, referrals or general assistance were provided if possible.

- Case Review with No Validity to Complaint: As cases are reviewed and interviews occur, it may be determined cases can be efficiently resolved with a few emails and explanation to the party requesting assistance. Generally, no follow-up is needed.

- Case Review with Confirmation: Case Review leads to more in-depth investigation into policies and procedures resulting in a need to address policies not followed, requests of information from DCFS on the case, and the CWO providing findings to parties involved. Resolution requires a greater time commitment, additional case-monitoring and ongoing contact with the party requesting assistance. A formal report may be done if warranted.

The Ombudsman manages cases timely by maintaining contact electronically and by phone while attending court, meeting with stakeholders and educating Arkansans statewide on the role of the program.

Contact Data and Statistics

Although data was initially documented in Excel worksheets, collecting and tracking comprehensive data on complex cases requires a database built for this purpose. After researching existing options in other states, UAMS IT was contacted. Because the CWO program is a division of ACCARDV, which is within UAMS, the database is being built by UAMS IT at no charge, saving the program thousands of dollars based on cost estimates provided by other states.

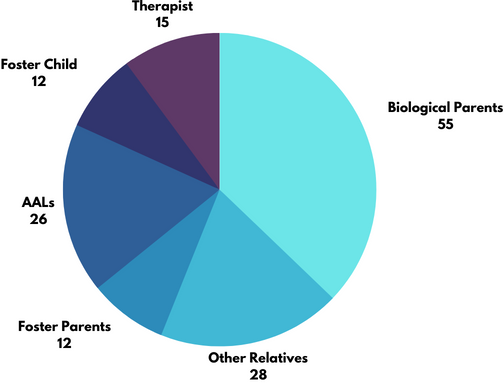

Number and Types of Contacts

There were a total of one hundred and thirty-five (135) cases received the first two years. Fewer than eight percent were unable to be reviewed or investigated because they fell outside the Ombudsman’s purview of the child welfare system. Referrals were made by the Ombudsman whenever possible. The remaining 125 cases were investigated, reviewed, and either unsubstantiated or substantiated. If unsubstantiated, the complainant was contacted and informed that upon further review their complaint did not have merit and referrals were provided if they needed further assistance. Often, they were encouraged to speak with their legal counsel as their issues often needed to be resolved through legal action. If the complaints were substantiated an email detailing the issues would be provided to the agency in question asking them to provide information on if the issue could be resolved, and if so, how the resolution would occur.

Requests for assistance or referrals often came from those involved in the child welfare case, maltreatment investigation or with knowledge of the case. For example, a biological parent involved in a Dependency-Neglect (DN) case, an AAL representing a child in a DN case, and a foster parent were all able to file complaints on behalf of their biological child, their client or their foster child to seek assistance from the Ombudsman.

Number of Requests

Other Relatives include grandparents, other blood relatives, and fictive kin

Other referrals or requests for help came from:

- Legislators

- Circuit Judges

- Behavioral Health Facilities

- School Counselors

- ACCARDV Commissioners

- Other State Agencies or Programs

Type of Requests for Assistance or Complaints

- DCFS Policy/Conduct: allegations that policy was not followed by DCFS employee, or conduct by DCFS employee was called into question

- Judicial Action: complaint regarding actions taken by a judge affecting a child welfare case

- Hotline Issues: maltreatment investigation questions, concerns, and allegations related to response from the Arkansas State Police Child Abuse Hotline

- Statute-related Issue: questions or concerns about a particular statute related to child welfare and its application; issues that can be resolved by referring someone to a statute

- Foster Child Placement: issue in regard to the placement of child currently in foster care

- Abuse Concerns: allegation that abuse is not being addressed through a maltreatment investigation or an open dependency-neglect case; may also be tied to concerns about the Child Abuse Hotline

- Disrupted Adoption: complaint that an adoption has been disrupted and services are needed by DHS and being denied; complaint that services are needed to prevent disruption and referrals are needed

- Grandparent or Fictive Kin Custody/Placement: complaint that family or fictive kin are being overlooked for placement in a dependent-neglect case

- Aftercare Issues: concerns over cases involving children that have chosen to stay in DCFS care after they reach the age of majority

- Foster Parent Application Process: complaints from foster parent applicants who have been denied the ability to open a foster home

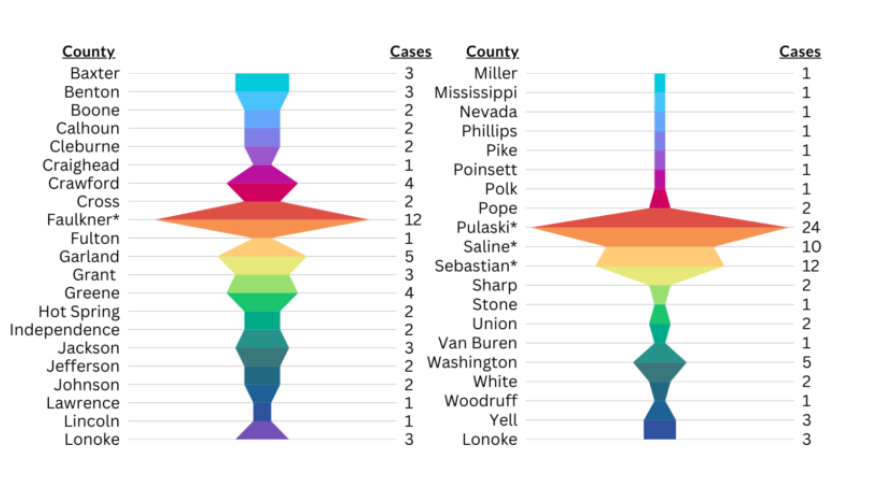

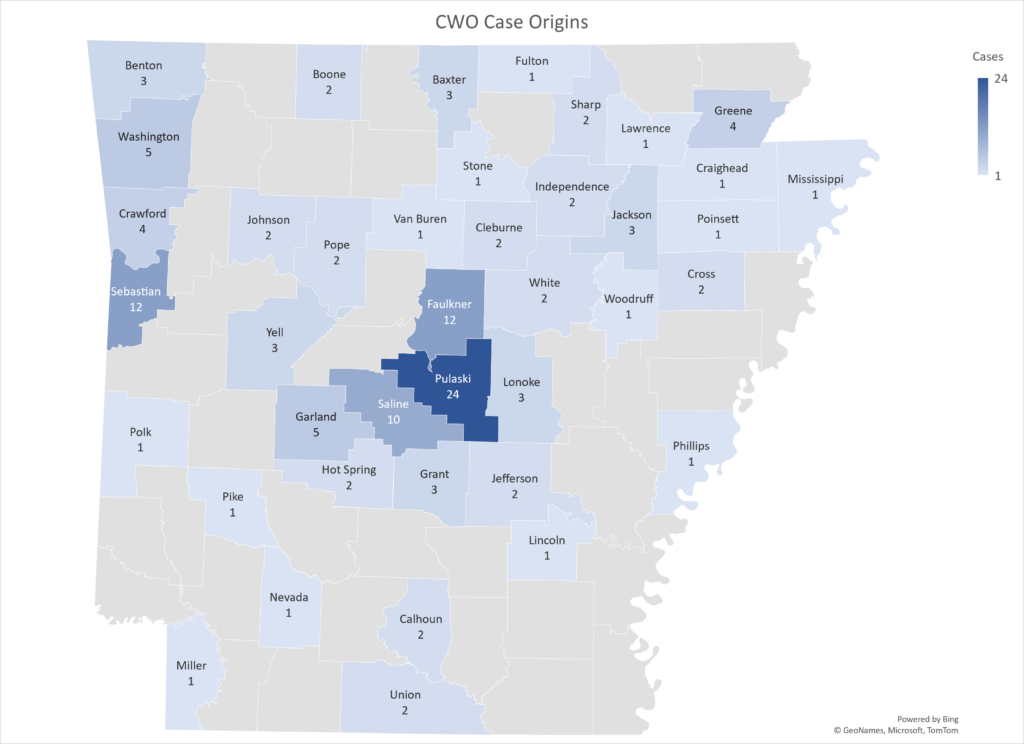

Requests for Assistance by County

Inquiries were received from 40 Counties listed below. One complaint was received from Texas, but as a domestic relations custody case, it was outside of the legislative purview of the CWO. Two in-state domestic relations cases were received but were referred to their attorneys for further assistance.

*42% of CWO cases originated from four counties. Of these 57 cases, 53 of them were related to DCFS policy or foster child placement.

Trends

As the program has grown, trends have been noted and directly addressed with agencies involved. Some issues may need to be addressed legislatively to be resolved appropriately. Ideally, as the CWO brings challenges within the system to the attention of stakeholders, barriers will be viewed through a lens of working collaboratively to improve the child welfare system to keep children safe and families intact when possible, while supporting foster and adoptive families, as well as the professionals in the field. The CWO addresses the following trends and examples with the sincere desire to work collaboratively to resolve issues and support families and staff.

One trend pertained to DCFS policies that were a challenge for caseworkers and other staff to adhere to due to staffing shortages and the remnants of COVID policies. These included policies pertaining to visits to foster homes, visits to the homes of the biological parents, responding to timely requests for assistance from foster parents, inquiring as to all possible family and fictive kin placement options, maintaining proper contact with foster children in residential care, and following all policies in regard to placement of foster children, especially those that are post-termination of parental

rights. DCFS was notified of all of these issues as they were reported to the CWO and throughout our investigations.

The other consistent trend was in regard to placement issues. The Ombudsman received thirty placement-related cases in 2021 and 2022 for DCFS children who were older, post-TPR, and had multiple issues that needed to be addressed, either behaviorally or psychologically. They are often repeatedly moved from one behavioral treatment facility to another. These cases were often brought to the CWO’s attention by the facility where the child was on a contract bed, or by an attorney ad litem who was fighting for the needs of their client. Out of the thirty cases that came through our office a few need to be mentioned.

One fourteen-year-old girl had 70 placements after five and a half years in DCFS custody. She came into care at age nine because she was sexually trafficked by her mother and grandfather. Two years later, that same girl is up to 89 placements. A sixteen-year-old boy who has been in DCFS custody for over ten years has had 77 placements that include the state hospital and DYS. Another young man had accrued 91 placements by the time he aged out of the system at 18. A thirteen-year-old mother came into care with her infant and spent the next three years in facilities. 23 of her 26 placements were in behavioral health facilities that did little for her mental or physical health needs. These children’s full stories cannot be told in a public annual report due to the confidential nature of the facts of each case. However, their stories need to be shared for real changes to occur. Their stories can be discussed in greater detail with legislators upon request.

“A thirteen-year-old mother came into care with her infant and spent the next three years in facilities. 23 of her 26 placements were in behavioral health facilities that did little for her mental or physical health needs.”

Success Stories

“I appreciate you looking into this and giving me a little more clarity on each situation. I can’t say that I am satisfied in the least. but I am more than satisfied with your response and obvious concern for the KIDS and their wellbeing. I wish there were more people like you in the system!” ~ relative that had nieces and nephews placed within her home through DCFS and had trouble getting medical records for them once they were in her custody. DCFS responded to the Ombudsman’s inquiry and said the issue would be addressed with staff to make sure that it did not happen in the future.

“You becoming involved has made communication with them so much easier. And I know it sounds trivial, but timely communication goes a long way to opening doors. Their refusal to communicate has been one the most frustrating things, so I am beyond thankful that with your help communication has resumed so at least there is the possibility of getting issues resolved. I know that there are hundreds of other kids in the system that aren’t being advocated for and are slipping through the cracks and that’s terrifying and unacceptable. Thank you for advocating for these kids who don’t have voices!” ~Foster Parent who was having communication issues with the caseworker assigned to their case.

I was just reaching out to let you know how thankful I am for you! The kids have been home for a month now and I know without a doubt that things would have never moved along without your help! We moved into our 4-bedroom house last month and the kids are transitioning back wonderfully! Whenever I tell my story I make sure to tell about how you helped my case tremendously! You’ll never understand how much you mean to me and I’m crying tears of joy because there were so many days that were filled with uncertainty but I had amazing people like you who helped me! ~Mother who was reunified with her children after a two-year period. She worked incredibly hard to be reunified with her children and never gave up even when the system did not support her.

Barriers to Investigation

Information Access

The largest barrier to investigations was not being able to access court cases through the statewide system, CourtConnect. The Ombudsman had to rely on attorneys connected to the case to provide court documents and case information that is easily accessible through CourtConnect. The Ombudsman legislation gives the Ombudsman the authority to access necessary case information, but CourtConnect access has not been granted.

Access was granted to the internal data system maintained by DCFS on all cases. Though this was extremely helpful in gaining information on a case, it was often incomplete. Due to overwhelming turnover in certain counties and the understaffing of many offices, information was often not up to date and rarely provided information on the status of the case in court. The Ombudsman having direct formalized access to both CourtConnect and the internal data system used by DCFS would create a more efficient process and reduce the need to make multiple contacts with DCFS staff and attorneys.

Recommendations

Legislative Recommendations

Ombudsman legislative requests:

- Access to CourtConnect and in-house DCFS database (it will be changing in the near future) be statutorily mandated (See previous section) Colorado allows the Child Protection Ombudsman the authority to request and review any information, records, or documents that ombudsman deems necessary to conduct a thorough and independent review. See C.R.S. 19-3.3-103. Statutory access would allow for consistent access, rules to be in

- place to address the confidential nature of the information and allow for efficiency in the investigation and review process.

- 2. Extend specific authority to investigate cases involving issues of child welfare in Juvenile Detention Centers

- Through a number of cases that involved foster children that had delinquent charges, it was discovered that a number of juveniles were being held in Juvenile Detention Centers (JDC) for many months though they had not been adjudicated of any delinquent charges. Even if a child was in DCFS custody, it did not mean that their case would not slip through the cracks of an overburdened system. Often the JDC was used as a holding place for a child waiting for evaluation at the state hospital or for a bed in a behavioral health facility. Arkansas Code Annotated § 9-27-327(b), states unless the juvenile or a party is seeking an extended juvenile jurisdiction designation, an adjudication hearing must be held within fourteen (14) days of the detention hearing when the juvenile is not released, unless waived by the juvenile or good cause is shown for a continuance. The current definition of “good cause” may need to be reviewed as it may allow children to sit in a JDC for more months than the law originally intended. **A report on a particularly egregious case is available for legislators upon request.

- 3. Mandate that children in foster care be provided with access to contact information to the Child Welfare Ombudsman

- Contact information could be provided to foster children through their attorneys, foster parents, or placements. In Texas, it is required that all residential treatment placements have the Ombudsman’s contact information posted in an area easily accessible by the child.

“Often the JDC was used as a holding place for a child waiting for evaluation at the state hospital or for a bed in a behavioral health facility.”

Summary

As the Ombudsman Division grows and handles more cases, we will need to collaborate with all stakeholders to address the issues and challenges that face the child welfare system. As we are able to document trends and challenges, we will be better situated to make recommendations to stakeholders on improvements to the system at the county and state level. Arkansas is a very diverse state and the challenges and issues that are faced by its families cannot always be handled with cookie-cutter solutions. It will require commitment and collaboration from all stakeholders to provide solutions that will work for all Arkansans.

During the first two years of the Ombudsman program, DCFS staff, attorneys ad litem, parent counsel, juvenile judges, therapists, and other stakeholders have been very responsive and available to the Ombudsman. All parties have worked with us to address the issues and complaints that have been brought to our office. Some issues have been resolved and others remain a challenge that all parties will need to address in the near future. We look forward to continuing to develop an independent review process that allows for recommendations to be made throughout the system and implemented in such a way that the best interest of children is protected and families receive the resources and services they need to be strong and resilient. The Child Welfare Ombudsman Division of the Arkansas Commission on Child Abuse, Rape, and Domestic Violence exists as an independent voice within the child welfare field in Arkansas. As we enter our third year of service to the people of Arkansas, we will continue to use that voice to serve the children and families who request our assistance.

Glossary of Acronyms

ACCARDV – Arkansas Commission on Child Abuse, Rape, and Domestic Violence

ARBEST – Arkansas Building Effective Services for Trauma

CASA – Court Appointed Special Advocates

CJA – Children’s Justice Act

CWO – Child Welfare Ombudsman

DCFS – Division of Children and Family Services

DHS – Department of Human Services

DN – Dependency-Neglect

JDC – Juvenile Detention Center

MDT – Multi-Disciplinary Team

QRTP – Qualified Residential Treatment Program

USOA – United States Ombudsman Association

Appendix

Enabling Legislation: A.C.A. § 20-82-211